Here is the second part of the fascinating insight of Hizbollah and what their strategy could look like in post-war Lebanon. Enjoy the rare and unique read. You can find both articles on

www.carnegieendowment.org in PDF format or here at Beirut Live.

Part Two: Accommodating Diplomacy and Preparing for the Postwar ContextBy Amal Saad-Ghorayeb

The adoption of United Nations Resolution 1701 and a formal cease-fire raise hopes for peace in Lebanon. Yet many questions exist about the viability of the settlement, questions whose answers will depend significantly on Hizbollah’s outlook, both about the diplomacy that has taken place as well as its own position in Lebanon coming out of the current conflict. The issue of Hizbollah’s disarmament remains a powerful potential logjam, one that could result in continued strife, either between Israel and Lebanon, or within Lebanon itself.

Partial Accommodation to the Lebanese Government’s Initial Diplomatic Stance Hizbollah consistently called for an immediate and unconditional cease-fire to the fighting that started after July 12—or as Hizbollah termed it: “an immediate end to Israeli aggression.” The party was opposed to the principle of a conditional cease-fire as part of larger peace package. As explained by Mohammed Fneish, Hizbollah’s Energy Minister, “the discussion of a comprehensive solution is in our opinion a cover for the aggression and allows the United States to appear as though it is making an effort at a time when it was waging war on us.”

Despite these objections, the party leadership assented to the seven-point comprehensive cease-fire plan put forward by the Lebanese Prime Minister, Fuad Siniora, soon after the conflict began. Hizbollah’s two ministers expressed reservations about the various elements of the plan, but the party felt compelled to agree to it for the sake of a common Lebanese front. According to Fneish, who took part in the cabinet deliberations, Hizbollah endorsed Siniora’s proposal “to prevent transforming our battle with Israel into a domestic battle, and to avoid being accused of hindering efforts which could have reduced losses for Lebanon.”

In another sign of accommodation with the Siniora government, Hizbollah ministers approved a Lebanese cabinet decision in the first week of August to mobilize 15,000 Lebanese army troops for deployment to the south in the event of a cease-fire and an Israeli withdrawal. Attempting to justify this move to the party’s rank and file, Hizbollah’s Secretary General, Seyyed Hassan Nasrallah, commended the cabinet’s decision as an act that would “greatly help Lebanon and its friends to press for amending the draft resolution which is being prepared at the Security Council.”

Skepticism about UN Resolution 1701

Despite Nasrallah’s espousal of a political resolution to the crisis, Hizbollah remains wary of diplomatic initiatives by the international community and harbors a particular mistrust of the UN Security Council. This mistrust is evidenced by Nasrallah’s characterization of Resolution 1701 as “unfair and unjust” for absolving Israel of its “war crimes and massacres” while holding Hizbollah “responsible for starting the aggression.” Throughout the conflict, Hizbollah repeatedly rejected any “humiliating conditions” being imposed upon it or Lebanon, regardless of “how long the confrontation lasts” or “how numerous the sacrifices may be.” In this vein, Nasrallah urged the government on several occasions, including in a speech on August 9, to remain “steadfast” and not acquiesce to American- Israeli demands in the negotiation process.

Despite Hizbollah’s criticisms, Resolution 1701 constitutes at least a partial diplomatic victory for the group insofar as it was an improvement (from Hizbollah’s perspective) on previous drafts that were rejected by both Hizbollah and the Lebanese government. As Nasrallah puts it, the end result was “the least bad” of all the drafts. Hizbollah would therefore “not be an obstacle to any decision taken by the Lebanese government” and would “abide by” any cease-fire agreement worked out by the UN Secretary General “without hesitation.” The resolution was approved by the Lebanese cabinet on August 12 and, by extension, by Hizbollah’s ministers, although they voiced a number of reservations.

Prospects for a Cessation of Hostilities

Resolution 1701 calls for a “full cessation of hostilities based upon, in particular, the immediate cessation by Hizbollah of all attacks and the immediate cessation by Israel of all offensive military operations,” after which the Lebanese government and reinforced up United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) forces are to deploy in the South, while Israeli troops withdraw “in parallel.” The implementation of this process is certain to be highly complicated and face a significant risk of failure.

Although both the Lebanese and Israeli governments acceded to Secretary General Kofi Annan’s call for a cessation of hostilities effective August 14, it is very possible that fighting will continue after that date, for two interrelated reasons: first, Israel is refusing to withdraw from Lebanon until international and Lebanese troops deploy; and second, Hizbollah intends to continue fighting as long as Israeli soldiers remain on Lebanese soil, as Nasrallah spelled out explicitly on August 12. This leaves an interim period of an estimated one to two weeks before UNIFIL troops are expected to arrive, during which the fighting is likely to flare up again.

Hizbollah’s First Clash with the Lebanese Government over Disarmament

In line with the Lebanese government’s seven-point plan, Resolution 1701 stipulates that the area between the Blue Line and the Litani River be manned solely by 15,000 troops each from the Lebanese army and UNIFIL. Although the UNIFIL force has not been granted peace-enforcement powers under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, it will have the right to “resist attempts by forceful means to prevent it from discharging its duties.”

As noted above, Hizbollah agreed to this arrangement when it approved the government’s seven-point plan. Hizbollah made this concession relying on the solid relationship it had developed with the approximately 1,000 Lebanese army troops stationed close to the southern border area since the Israeli pullout in 2000, and the similar modus vivendi it achieved with the 2,000 UNIFIL forces stationed there since the early 1980s. Hizbollah also assumed that the Lebanese army’s role would be to secure Lebanon’s border, not Israel’s, as demonstrated both by Nasrallah’s recent assertion that the Lebanese army “are not forces that take orders from enemies” and Fneish’s assessment that “the army’s role would not be to protect Israel and it wouldn’t deploy according to Israel’s security needs.”

Hizbollah did not equate the Lebanese army’s deployment with its own disarmament and hence saw no potential clash between its armed forces and the army. This assumption was reinforced by there being nothing in the cabinet-approved plan explicitly suggesting that Hizbollah would be expected to disarm. Moreover, the fact that Resolution 1701 does not resolve the dispute over Shebaa Farms (the Secretary General is to present a proposal on this issue to the Security Council within 30 days of the date of the resolution) also gave Hizbollah what it viewed as further assurance that the Lebanese government would accede to its maintaining arms. A source with close links to the party suggested in a recent interview that Hizbollah was relatively confident that the government would be bound to its policy statement of July 2005, which clearly legitimized Hizbollah’s “right” to “complete the liberation of Lebanese territories,” meaning Shebaa. Hizbollah clearly envisaged an arms management as opposed to an arms decommissioning scenario whereby its arms would remain hidden, and hence deactivated, save for occasional attacks on the occupied Shebaa Farms area, which could be launched from its bases behind the Litani River.

These assumptions were shaken on August 13, however, in the immediate aftermath of the issuance of Resolution 1701 when cabinet members of the ruling majority called for a special session to deliberate on Hizbollah’s disarmament preceding the deployment of the Lebanese army and UNIFIL. Hizbollah’s ministers refused to discuss the prospect of disarmament at the current time, for various reasons, including that Shebaa’s status would remain unresolved for another month. According to a source close to the Lebanese army command, the army command refuses to dispatch troops to the south if their mandate is rejected by Hizbollah.

Such a decision is not surprising given that an estimated 40 per cent of army conscripts are Shiites, while the army is known to be sympathetic to Hizbollah and enjoys good relations with Hizbollah’s military command. Moreover, it is likely that the army is keen to avoid a split in its ranks as has occurred in the past. Whatever the outcome of this deadlock might be, it is bound to complicate efforts to dispatch international forces to the area, while the political polarization underlying the deadlock may intensify in the near future.

Hizbollah’s Broader Rejection of Disarmament

Resolution 1701 reiterates the need to implement Resolutions 1559 and 1680, which call for the disarmament of Hizbollah (without mentioning Hizbollah by name), as part of a comprehensive and permanent cease-fire plan. In order to better appreciate the difficulties inherent in any effort to disarm Hizbollah in a postwar scenario, an examination of the party’s motives for maintaining its arms and refusing the integration of its military forces into the army is needed.

Most campaigns for Hizbollah’s disarmament are premised on the argument that a sovereign democratic state has to possess a monopoly over the use of force. Although Hizbollah has failed to publicly articulate an intellectually coherent counter-argument to these calls, party officials have attempted through various statements to justify Hizbollah’s armed status, including in interviews conducted by the author in June of this year.

According to Fneish, “the resistance did not emerge when the state was strong and in a position to protect its borders; it did not cause the weakness of the state. The resistance emerged because the state was already weak, it came because the state failed.” He adds that had it not been for the armed resistance, and the liberation of Lebanon from Israeli occupation, there would have been “no return of the state to the south.” In this view, the state lacked sovereignty because of successive Israeli invasions and occupations, not because of Hizbollah’s arms. Had the state assumed its role as a sovereign power and evicted Israel from its territory, there would have been no need for the resistance. Ali Fayyad, Politburo member and director of a think tank closely affiliated with Hizbollah, adopts a similarly utilitarian argument: “Society is more important than the state because the state is meant to serve society … when the state fails in carrying out some of its functions, society must help the state in carrying them out, even if the state doesn’t ask.” Thus, although Hizbollah officials agree “in theory” that a state must have a monopoly on the use of force, in practice they do not. In the words of Fneish, “confronting the danger to the country’s destiny is more important than the theoretical incompatibility of such means with the state’s authority.”

But this incompatibility is more than just theoretical for many critics of Hizbollah who see the organization as constituting a “state within a state.” In light of this, various proposals have been floated, which center on integrating the Hizbollah’s military capacity into the Lebanese army, such as one put forth by Terje Roed-Larsen, special UN Envoy for Implementation of Security Council Resolution 1559 on Lebanon. Asked in a June interview what he thought of Roed-Larsen’s proposal, Sheikh Nai’m Qassem, Hizbollah’s Deputy Secretary General, asserted that it “appears to be a solution but in essence, its aim is to eliminate the resistance,” and for that reason, its implementation was “out of the question.”

In May, Nasrallah publicly ruled out such a merger as well, arguing that “it is not a realistic option because this will weaken the Lebanese position in facing the much superior Israeli army.” He contended that even if the army had the needed manpower and budget to bolster its forces, the United States and other Western powers would not agree “to sell us qualitative arms that would guarantee air cover for the army.” Given these obstacles, Hizbollah’s armed forces are the only way of creating a “balance of power” with the Israeli Defense Forces.

Hizbollah asserts other grounds for objecting to the integration of its armed forces into the army. One such argument is that the “margin between the Resistance and army” is of benefit to the state insofar as it does not have to bear direct responsibility for any of the resistance’s activities. As Nasrallah pointed out earlier this year, “when any resistance under the army fires a single bullet, then the ministry of defense … and the entire state would be subject to direct attack.” For these and other reasons, Hizbollah offers few concessions on its arms other than “coordination without integration.” The farthest Hizbollah officials have gone is to suggest that Hizbollah’s armed forces would become a “reserve army,” which would coordinate with the Lebanese army on matters of strategy but not tactics. However, this would amount to little more than “calling resistance by another name,” to use Qassem’s terminology, given that Hizbollah’s military activities would remain under its own command.

It follows from this that Hizbollah is not willing to disarm in the foreseeable future. As Nasrallah has spelled out on several occasions, the party will remain armed for “as long as Israel remains a threat to the country.” In a speech earlier this year, Nasrallah suggested that only a “comprehensive settlement which would bring an end to the war” could neutralize that threat. From Hizbollah’s perspective, the security of Lebanon remains inextricably tied to the Arab-Israeli conflict, regardless of Israel’s fulfillment of specific Lebanese demands. Fneish articulates this view in stating that, “the problem wouldn’t be solved if Israel simply withdraws from Lebanon,” but would continue until a just and comprehensive regional agreement is in the offing. For Qassem, “when Palestinians are being killed on a daily basis on our very doorstep and when 300,000 or 400,000 Palestinians remain in Lebanon and cannot return to their country … this is aggression.” Asked to specify the exact conditions under which Hizbollah would no longer view Israel as a threat and contemplate disarmament, Qassem answers, “let’s not talk about the reaction but the action…. If the Israeli danger disappears one day and I have no idea how it would disappear, then the resistance which was a reaction to the Israeli danger would no longer be present. The struggle is therefore open so long as Israel is aggressive in its presence and existence.”

Hizbollah officials have insinuated on various occasions that the party might hold on to its arms indefinitely due to what it perceives as the perpetual threat posed by Israel. For example, Nasrallah described Israel as a “permanent threat which could turn into aggression at any time,” in the same breath as his utterances on a comprehensive settlement. In perhaps one of the clearest indications of Hizbollah’s view of the nature of the Israeli threat and hence Hizbollah’s determination to retain its arms, Qassem affirmed as recently as two months ago that, “our opinion is that Israel’s existence itself is a danger. Because the origins of Israel lie in the occupation of land and the violation of others’ rights. This is aggression. Every single experience we have had since 1948 until now is an experience of aggression, expansion, wars and displacement, imprisonment and killing. Parts of four countries were occupied under the banner of Israel’s existence.”

Hizbollah’s Postwar Plans

In the view of many observers inside and outside the region, including some in Israel, Hizbollah has effectively emerged as the military victor in this war by having survived and by inflicting losses against Israel throughout the conflict. Some Lebanese politicians representing the “March 14” political camp, as well as many non-Shiite Lebanese, have voiced fears about the political implications of a victorious Hizbollah. In an attempt to allay such concerns last month, Nasrallah responded: “I conclusively answer by saying, first of all, Lebanon and its people had an experience with how this resistance acted after the victory in 2000. Second, I assert from now on that victory will be for all of Lebanon.” The Hizbollah leader was referring to similar fears that were expressed in the aftermath of Hizbollah’s liberation of south Lebanon from Israeli occupation in 2000. As elaborated by Hizbollah Politburo member Ghaleb Abou-Zeynab, “the fear is that Hizbollah would change the entire political equation if it triumphs to eliminate others. There will be political changes but we have no intention of destabilizing the situation.”

These “political changes” that Hizbollah envisions are two-fold. The first relates to Lebanon’s political identity and foreign allegiances. Nasrallah alluded to the desired change when he recently urged the government “not to forget” how the U.S. administration failed it in its time of need, and cautioned those who continue to count on U.S. support. In an expansion of this stance, Abou-Zeynab claimed that those “who had previously relied on the outside for their policies or U.S. support for change, now have to rethink this in light of the new reality.” Hizbollah is making an assertive claim to Lebanon’s political identity, as exemplified by Abou Zeynab’s statement that, “Lebanon will be removed from the U.S.-French orbit.” By the same token, Nasrallah has vowed that “Lebanon will not be one of the locations of the ‘new Middle East.’”

The second change concerns a new hardening on disarmament. Now that Hizbollah has shown that Israel’s powerful, U.S.-backed military was unable to disarm it, it believes that nobody else can, least of all the weakened Lebanese government. Qomati boldly declared that the “resistance is a red line for us, handing [in] our arms is out of the question, even if Shebaa is liberated.” This view is likely shared among the approximately 96 percent (according to a poll carried out in Lebanon last month) of Lebanon’s Shiites who support Hizbollah. The hundreds of thousands of Shiites who have been displaced from predominantly Shiite areas are likely to be more united as a community, as well as angry and radicalized vis-à-vis Israel, and thus even more favorable to Hizbollah maintaining arms than in the past.

In light of these facts, the consequences might be dire if the Lebanese government ardently pursues the disarmament of Hizbollah. In the worst case scenario, civil strife would occur and the state would collapse. In the best case, all Shiite ministers would withdraw from the cabinet, leading to the government’s collapse. Ultimately, the ruling majority is likely to be faced with a troubling dilemma: either a state within a state or a state within a failed state.

Amal Saad-Ghorayeb is an assistant professor at the Lebanese American University in Beirut. She writes regularly on Lebanese politics and is the author of Hizbullah: Politics and Religion

(another of the infamous Johnnie Walker ads in Lebanon prepared by the local office of Leo Burnett)

(another of the infamous Johnnie Walker ads in Lebanon prepared by the local office of Leo Burnett)  (another of the infamous Johnnie Walker ads in Lebanon prepared by the local office of Leo Burnett)

(another of the infamous Johnnie Walker ads in Lebanon prepared by the local office of Leo Burnett)

The war between Israel and Hizbollah might be over for now, but a new war within Lebanon has just started. We are facing mountains of problems from all sides - be it economically, socially, politically or enviromentally.

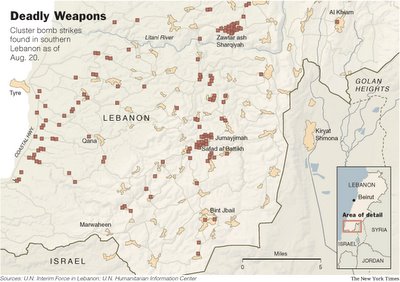

The war between Israel and Hizbollah might be over for now, but a new war within Lebanon has just started. We are facing mountains of problems from all sides - be it economically, socially, politically or enviromentally. Amnesty International released its report on the war in Lebanon in which it clearly condemns the Israeli aggression as war crimes. It states that Israel deliberatly targeted civilians and the country's infrastructure as part of its military strategy. Israel's statement that it was targeting Hizbollah who were using civilians as human shields "rings hollow," stated the respected organization. It's time that IDF stops acting as a bully and starts abiding by the Geneva Convention. Why did Israel target a milk factory for example? RS visited the bombed site in the Bekaa yesterday and he will update you on that soon. Some sources claim that the Lebanese milk factory had won a profitable EU contract recently, beating an Israeli milk factory who came in second place. If this is true or untrue, the question still holds: why a milk factory?

Amnesty International released its report on the war in Lebanon in which it clearly condemns the Israeli aggression as war crimes. It states that Israel deliberatly targeted civilians and the country's infrastructure as part of its military strategy. Israel's statement that it was targeting Hizbollah who were using civilians as human shields "rings hollow," stated the respected organization. It's time that IDF stops acting as a bully and starts abiding by the Geneva Convention. Why did Israel target a milk factory for example? RS visited the bombed site in the Bekaa yesterday and he will update you on that soon. Some sources claim that the Lebanese milk factory had won a profitable EU contract recently, beating an Israeli milk factory who came in second place. If this is true or untrue, the question still holds: why a milk factory? (The above flag is that of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards; the lower of Hezbollah)

(The above flag is that of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards; the lower of Hezbollah) Even though we all know that Hezbollah is trained and equipped by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, it is rather surprising to see the shocking resemblance in their flags. Apart for the colors and the Arabic writing, the rest of the flag (hand, weapon, globe and leaf) are exactly the same.

Even though we all know that Hezbollah is trained and equipped by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, it is rather surprising to see the shocking resemblance in their flags. Apart for the colors and the Arabic writing, the rest of the flag (hand, weapon, globe and leaf) are exactly the same. This week-end we were above the clouds in Faqra resort (as seen in pic). RS and I, along with a member of another blog (arabisraelipeace.blogspot.com) decided we needed a really relaxing time-off from the city, the news and the politics. What better way then to head to the peaceful mountain resort where there is no humidity or heat. It was perfect timing as the war was over and we really deserved some quiet from the 30+ day nightmare we lived through continously.

This week-end we were above the clouds in Faqra resort (as seen in pic). RS and I, along with a member of another blog (arabisraelipeace.blogspot.com) decided we needed a really relaxing time-off from the city, the news and the politics. What better way then to head to the peaceful mountain resort where there is no humidity or heat. It was perfect timing as the war was over and we really deserved some quiet from the 30+ day nightmare we lived through continously. (Clean up crew in Dahieh)

(Clean up crew in Dahieh) Sunday the 13th of August – two days after Resolution 1701 was unanimously agreed on and one day before the cease-fire became effective. Hopes in Lebanon, and surely in Israel, were high. Will we have quiet? Will this lead to a lasting peace? My instincts tell me no, unfortunately. Let me share with you why.

Sunday the 13th of August – two days after Resolution 1701 was unanimously agreed on and one day before the cease-fire became effective. Hopes in Lebanon, and surely in Israel, were high. Will we have quiet? Will this lead to a lasting peace? My instincts tell me no, unfortunately. Let me share with you why.